Last fall I got an unexpected message from Arthur Nager. Art had taught at the Center of the Eye workshop in Aspen in the early seventies, and he wanted to show me an extraordinary set of images he had taken at the Divine Light Festival, a one-day event that took place outside of Montrose in July 1972.

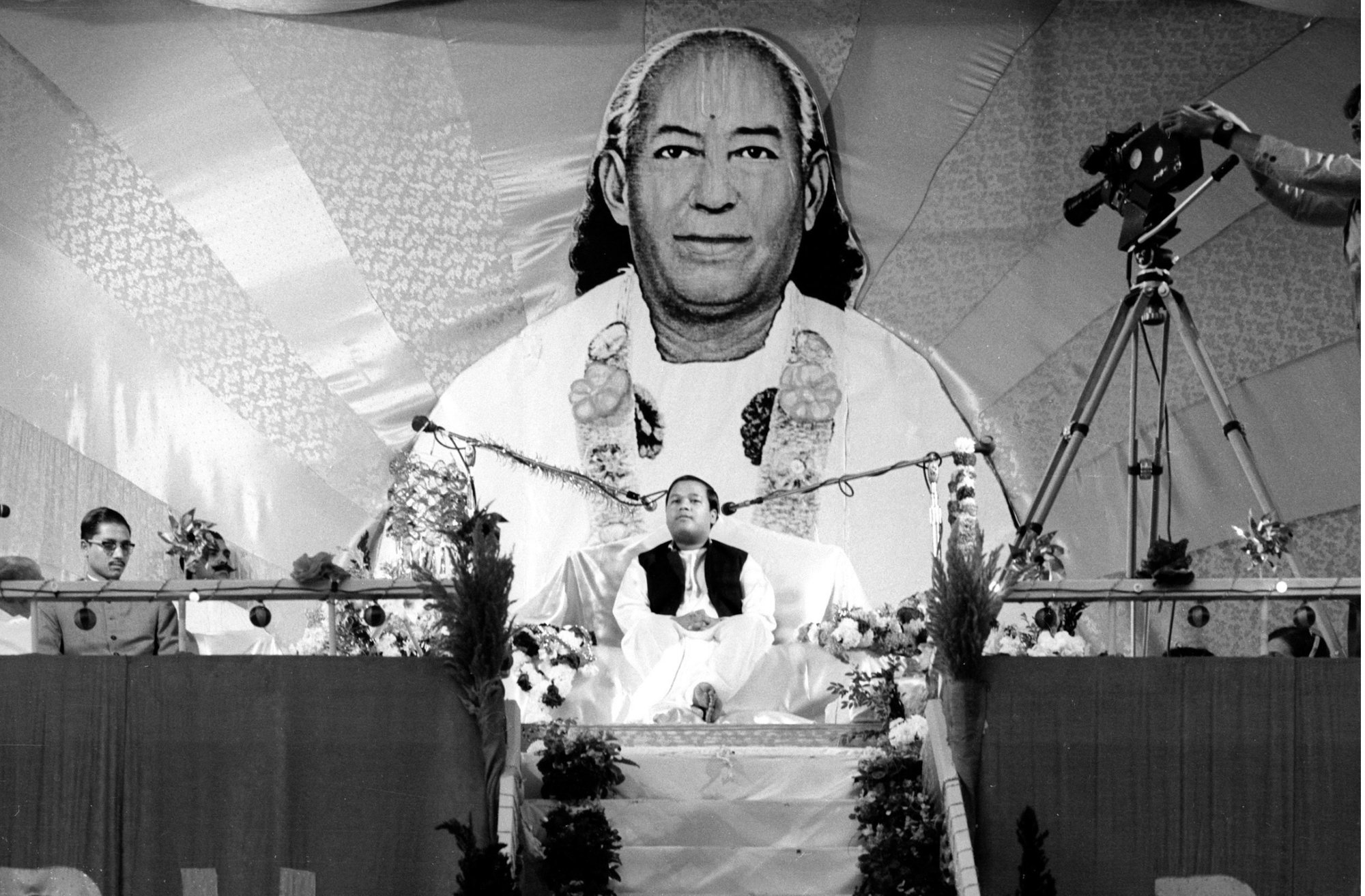

The festival was organized to herald the “Perfect Thirteen-Year-Old Master,” aka the Guru Maharaj Ji, now known as Prem Rawat. Something that struck me even before I saw his images was that I, too, may have seen the Guru Maharaj Ji at the Glastonbury Festival in England in 1971. But I might be mistaken, for there were a lot of pudgy young gurus beguiling the counterculture back then.

As will become obvious, Art took many insightful, quirky, and affectionate pictures in Colorado during his times here. As we talked I also learned that he had been good friends with Syl Labrot, a brilliant artist who lived in Boulder in the fifties and created a very influential hand-pulled book of color imagery titled “Pleasure Beach” in 1977. I wrote about Syl some time ago, and I’m pleased to be able to add Art’s recollections of him here.

Art received his MFA degree from the Visual Studies Workshop. After his first summer at CoE he taught in the Colorado public school system at Aurora, returned to CoE for a second summer, and in 1973 took a teaching position as Director of Photography at the University of Bridgeport. He left in 1990 to establish a design firm in Fairfield, CT, where he still lives. This is an abridged version of an interview we recorded in January 2022, via Zoom.

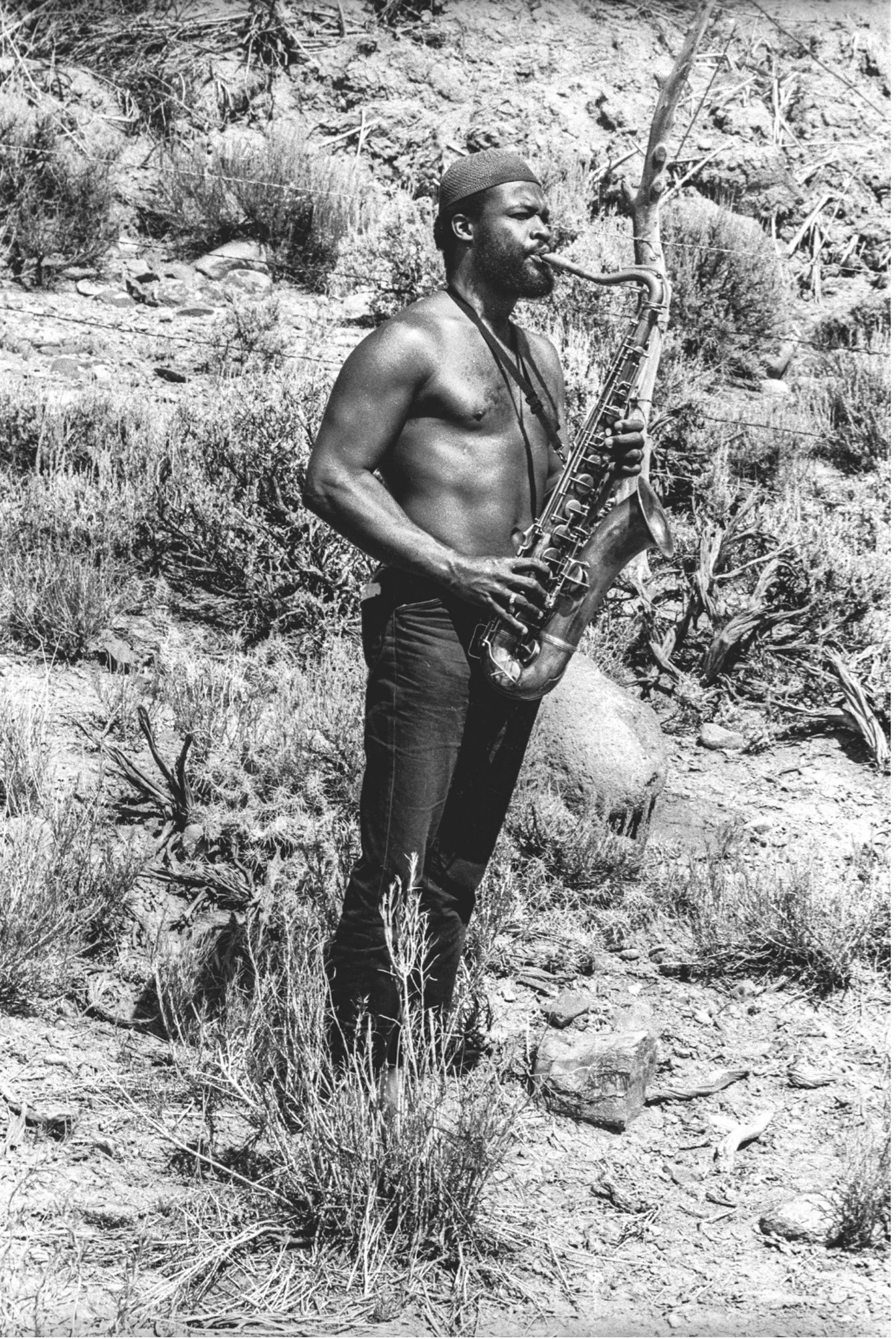

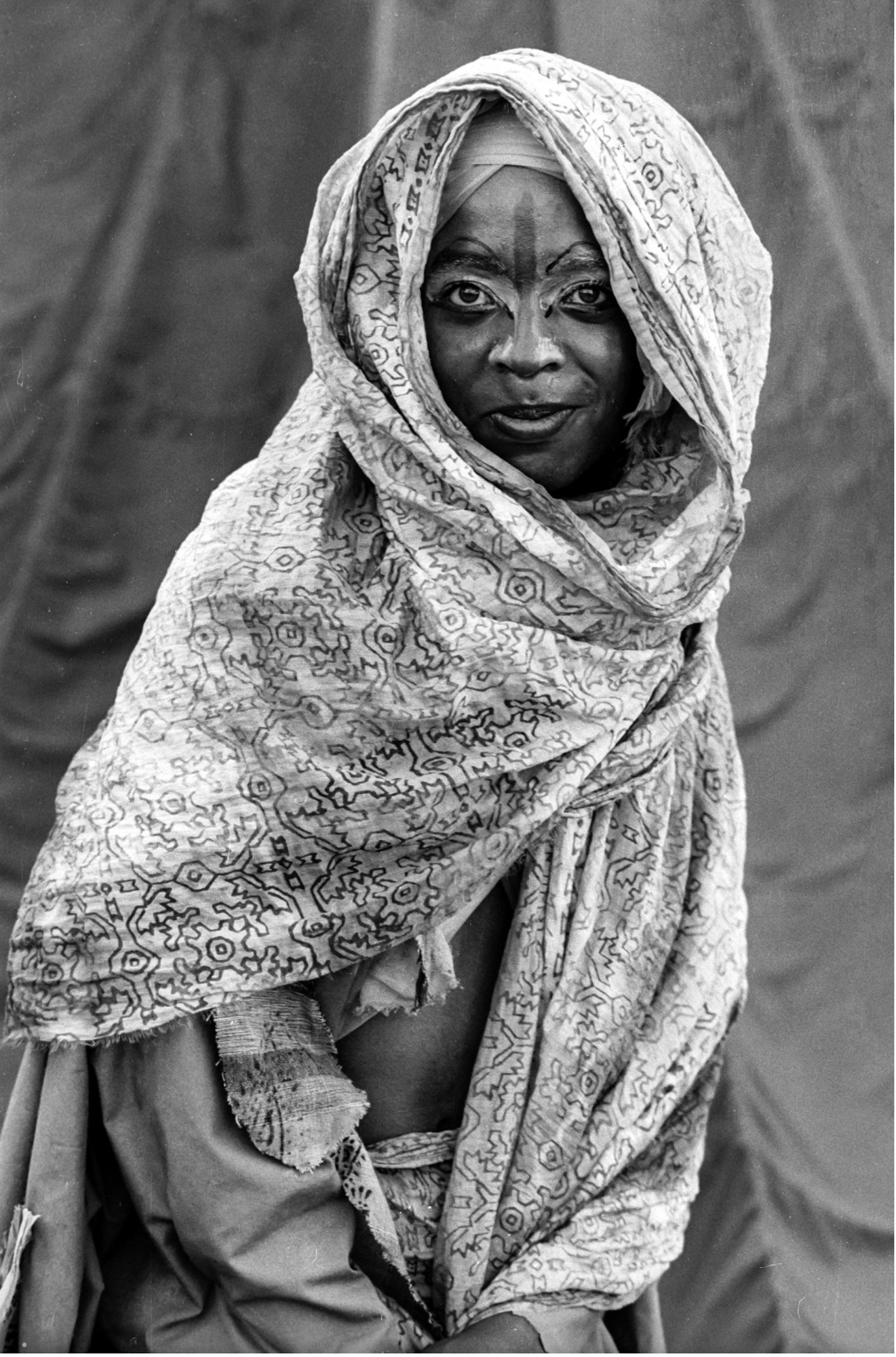

Arthur Nager: Divine Light Festival, near Montrose, CO, 1972

RJ: When and where was the Divine Light Festival, exactly?

AN: It was July 27, 1972. At the time I was still exploring different approaches, including view camera landscape work and portraits. None of it struck a chord and I gravitated to finding events or locations that I believed would be of interest. My strongest work involved documentation with a personal point of view, so when I heard about the Divine Light Festival I realized it was an opportunity to capture something of interest.

The event was held in the desert outside of Montrose and lived up to my expectations. I attempted to record the bizarre intersection of East and West celebrated by young counterculture kids from all over the U.S. along with Eastern Indian spiritual teachers. There was a surreal, almost Fellini-like atmosphere, with numerous photographs of young Guru Maharaj Ji plastered under umbrellas to protect his image from the sun. The location of the festival in the Montrose desert was chosen to herald the incarnation of the young deity and that’s the way his followers viewed it. They put on a passionate display of devotion which I attempted to capture.

This event was part of the first visit made by the “Perfect Thirteen-Year-Old Master” to the U.S. and was to set the stage for a giant three-day rally held at the Houston Astrodome in 1973. The Astrodome event was to be the kickoff of the New Millennium and the Revelation but it attracted fewer than the 100,000 devotees expected and signaled the fading enthusiasm for Guru Maharaj Ji. The former Guru Maharaj Ji, now known as Prem Rawat, currently leads a secular peace foundation.

RJ: I imagine Winogrand, Friedlander, those kinds of “snapshot” street photographers, were a big influence on you?

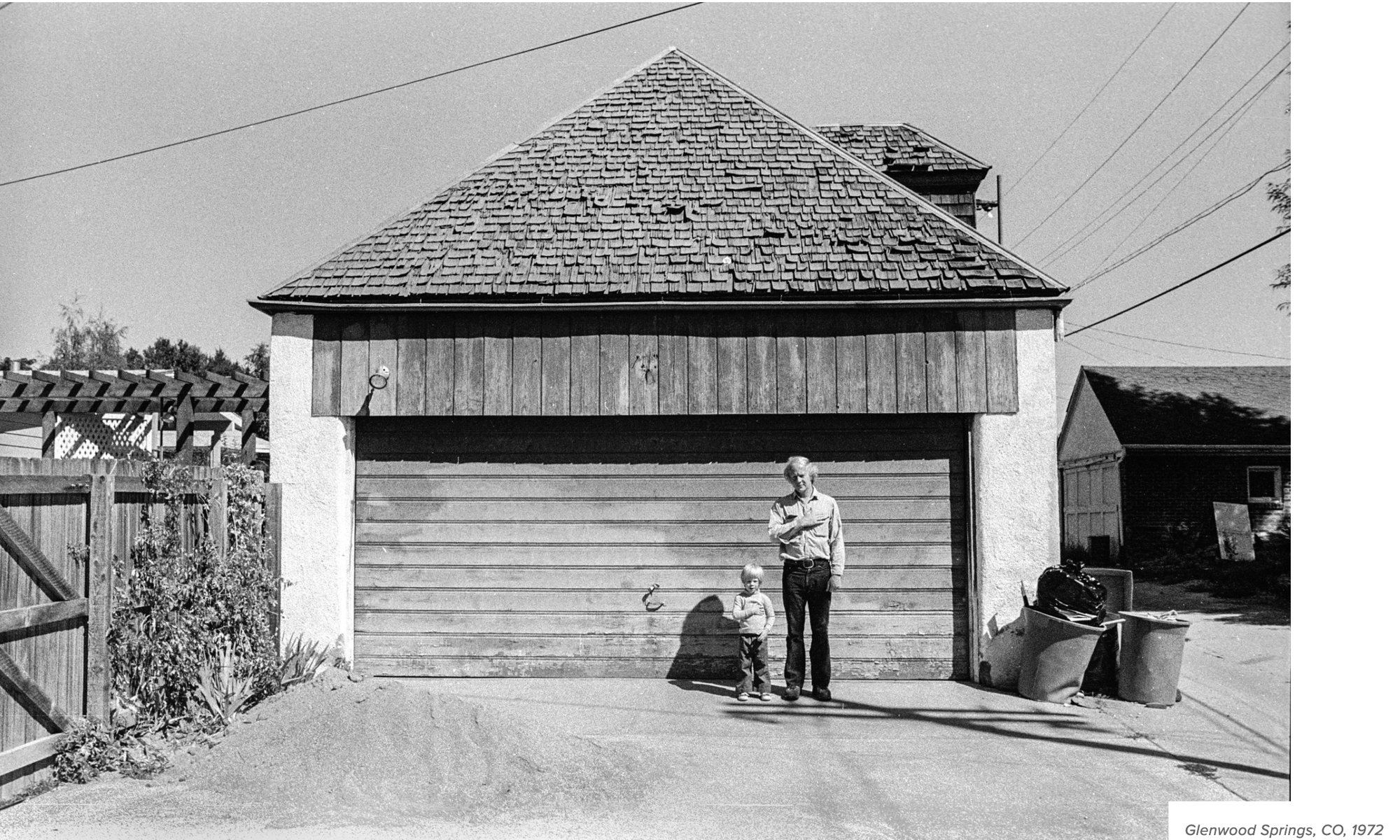

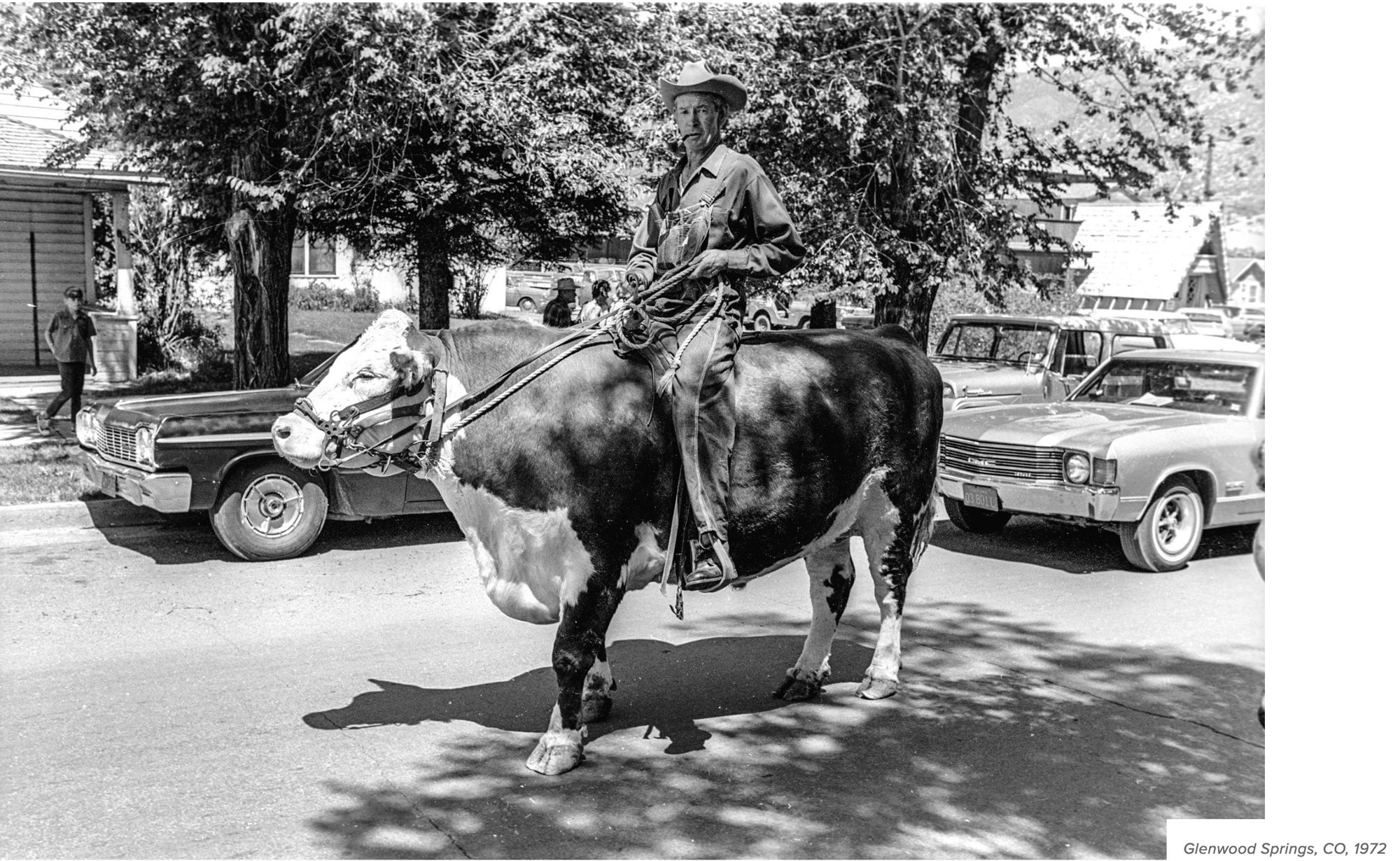

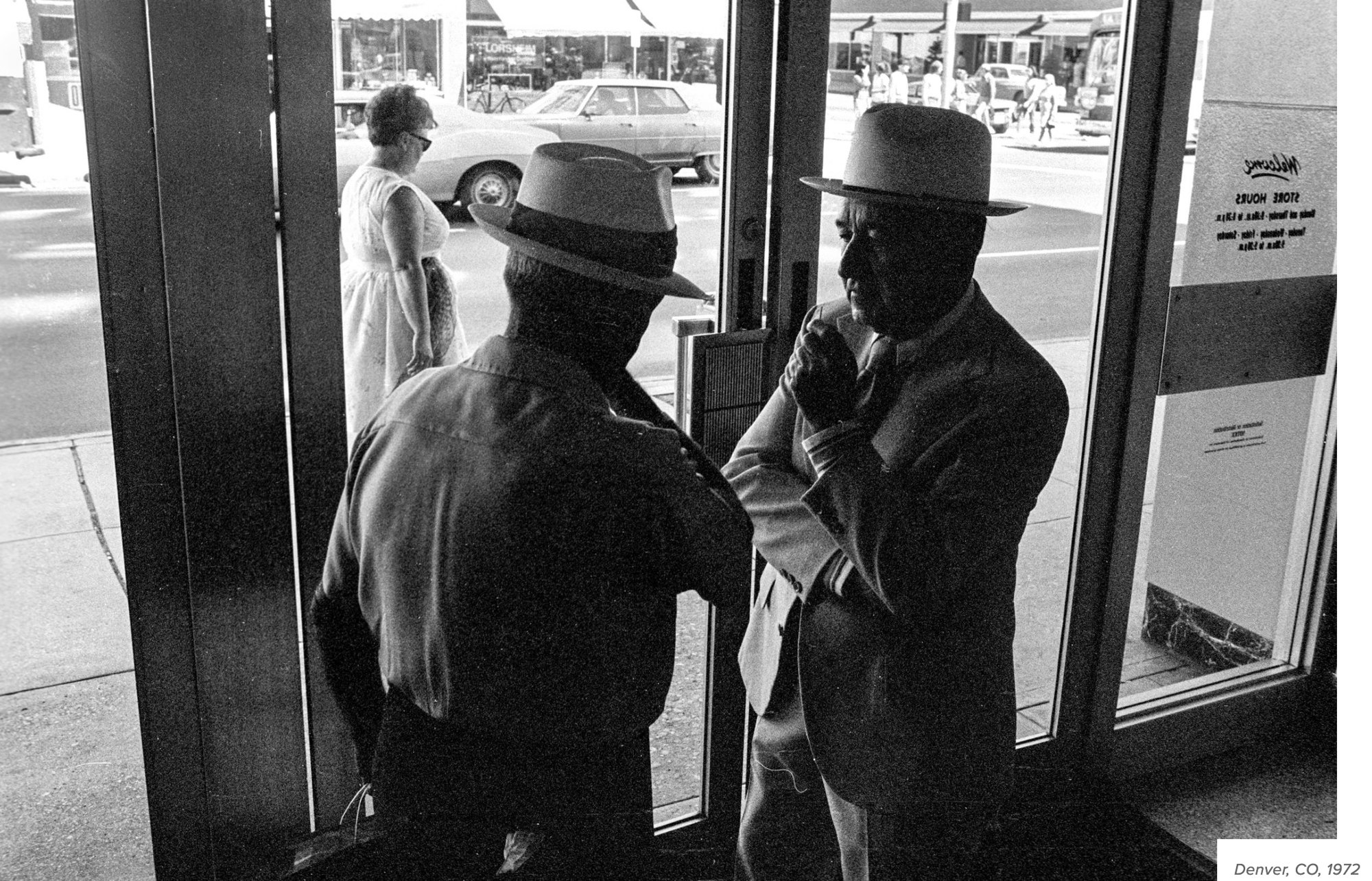

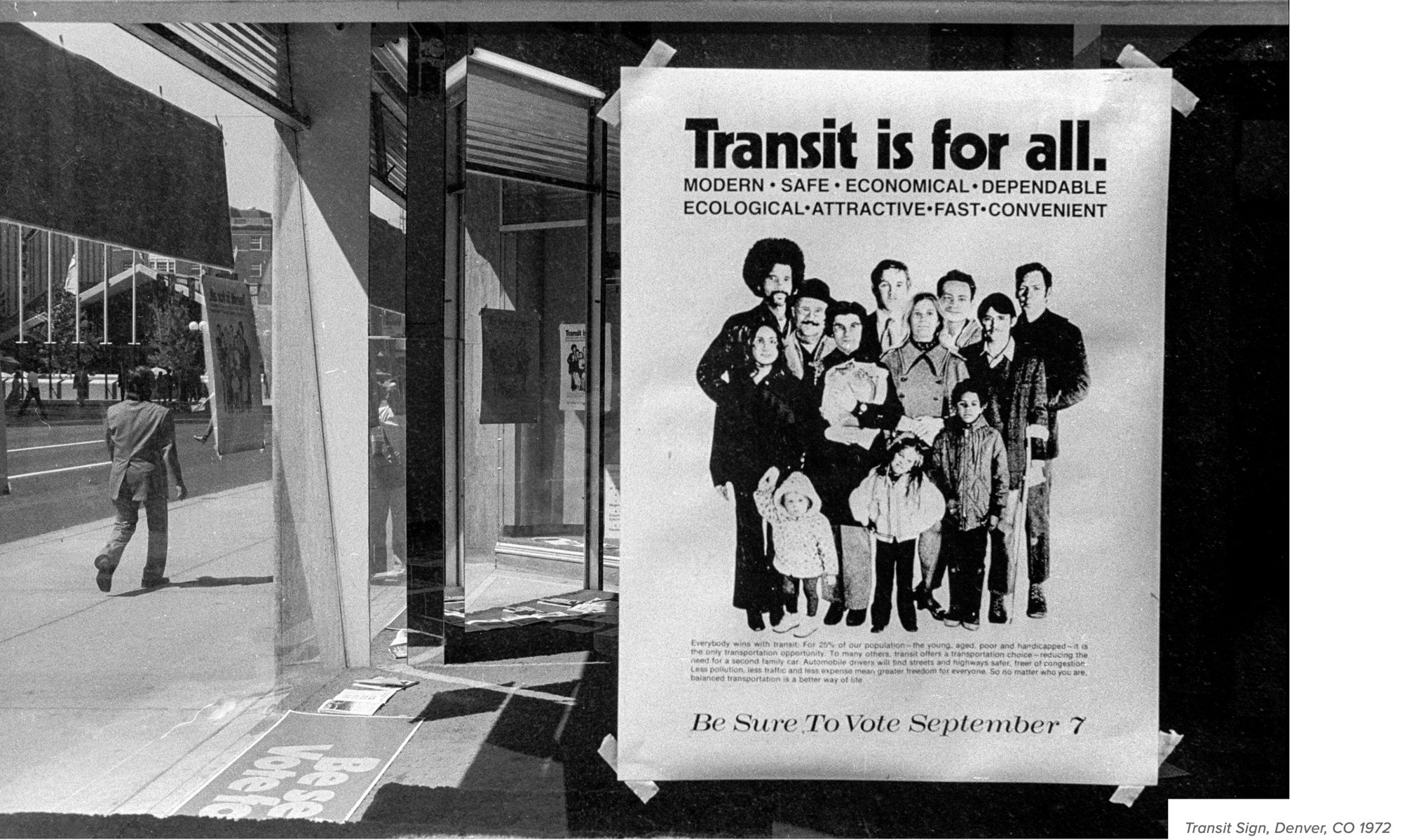

I was influenced by many of the photographers whose work I was seeing including Winogrand, Friedlander, and Diane Arbus. I was impressionable but I had a point of view that I think was reflected in the work I did back then. I worked on a number of other projects in Colorado including a series documenting the Strawberry Days Festival in Glenwood Springs (below). It is one of the oldest street festivals in the country and the photographs, capture an event in the seventies snapshot aesthetic. Like the Divine Light photographs, I was interested in the intersection of two cultural traditions—in the Strawberry Days series it’s the celebrated Old West and life in a contemporary All American Colorado town.

While living in Colorado, I periodically returned to Queens to visit my family and worked on a number of projects, including one which led to the release of a recent book—Wrestling Sunnyside Garden Arena, November 27, 1971 (available at www.sunnysidegardenwrestling.com).

From 1973 on, I traveled a lot and the work covered trips across the U.S. and up to Victoria and Vancouver. The road trip photographs from Las Vegas, Santa Cruz, and San Francisco are also very seventies images and interspaced are photos that do reflect the New Topographic aesthetic. So, a lot of the hotel, motel, and vacant desert landscapes photographs are characteristic of what was in the air at the time.

My appreciation for the New Topographics aesthetic and a conceptual approach to photography also played a role in my friendship with Syl Labrot. Part of the requirement to obtain an MFA degree from VSW was to present and defend your work to the faculty and students. Moving to Connecticut enabled me to reconnect with Syl who had moved to NYC where he had bought and renovated a loft. As my advisor, Syl provided advice and support for the work I was doing at the time. So my projects in Colorado, which were destined to be my presentation for my final degree, included that series on Guru Maharj-ji.

Arthur Nager: Three women, Aspen, c. 1973.

In addition, I had a series that I photographed in the center of Aspen, where I set up a portable photographic booth to photograph people on the street in a clinical way, where the background is just white and you just see individual faces (above).

RJ: People would come into the booth to be photographed?

AN: Yes. Just people in the booths to be photographed. But this project, like the New Topographics work, didn't fall into the traditional category of street photography. Syl felt that I might have a problem trying to defend this since he believed the audience might not have been geared toward this type of work. As it turned out I wound up getting the degree, but he was supportive of the idea of looking at alternative approaches to the medium and being adventurous about the projects I was considering. Syl’s move to NYC really solidified our relationship. I was showing him work and seeing work that he was doing. He had been, as you know, a calendar photographer in the past, but he was already a very good painter. He had beautiful large paintings, I think, mostly abstract, and he was interested in the intersection of painting and photography.

Leaf from “Pleasure Beach” by Syl Labrot. VSW Press, 1977. Arnold Gassan Collection, Center for Creative Photography.

The book focused on a couple of themes in his work, including Pleasure Beach was an abandoned amusement park outside of Bridgeport, and also photographs of his wife, Barbara. So it was an interesting amalgam of his interests in painting, the nude, and fantasy. It was a beautiful book. I have a copy that he signed for me. Syl was talented, worldly, sophisticated, and a genuinely sympathetic, great soul. And I felt very connected to him. His passing, which came really suddenly, was tragic and a major event for me.

RJ: You knew Hank Wessel in graduate school, several years before he was included in New Topographics. Was he an influence on your architectural photography?

AN: Yes, definitely. I had a great affinity for his approach. Along with being students at Visual Studies we both also wound up teaching at the Center of the Eye in Aspen. I visited Hank in California a few times and really admired his work as a photographer and teacher. His passing was another great loss.

I imagine that most photographers working in the seventies were aware and often influenced by what they were seeing at the time, and I’m no exception. Part of the dilemma for any photographer is recognizing how they are influenced by other photographers while working to establish a personal point of view. I didn't want to become another Garry Winogrand or Hank Wessel, but what I appreciate about the medium is the diversity and options available when making photographs. It’s important to understand what other photographers are doing, but the challenge is figuring out how to chart one’s own creative path.

END

All images courtesy of Arthur Nager unless otherwise noted. Art’s Instagram page is @arthurnager. His website is www.arthurnager.com. Art’s most recent book, titled Wrestling Sunnyside Garden Arena, November 27, 1971 is available at : www.sunnysidegardenwrestling.com.

The Colorado Photo History blog is the online presence for “Outside Influence,” a book project by Rupert Jenkins. As always, please leave a comment or a suggestion for future posts, and visit #Colorado Photo History on Instagram and Facebook.

#coloradophotohistory @coloradophotohistory #outsideinfluence #arthurnager @arthurnager #centeroftheeye #pleasurebeach #syllabrot